This article was originally posted on truthout.org, and you can find it here.

As the holiday season unfolds, filled with joy, family gatherings, and festive traditions, it’s easy to overlook the harsh realities faced by many who are unable to share in these celebrations. For Edwin Rubis, a man who has spent over 26 Christmases behind bars for a nonviolent marijuana offense, the season is a painful reminder of separation, isolation, and the unrelenting consequences of outdated drug policies.

In this deeply personal account, originally published on Truthout, Edwin sheds light on the grim realities of prison life during the holidays—where joy is scarce, meals are meager, and the emotional weight of lost time with loved ones feels unbearable. Yet, even in these bleak circumstances, Edwin’s story resonates with resilience and hope as he reflects on the small mercies he clings to amidst the injustice of his incarceration.

Beard Bros Media is committed to elevating voices like Edwin’s, shining a light on the urgent need for cannabis policy reform, and advocating for the freedom of those who continue to pay the price for a failed war on drugs. Edwin’s story is not just a reflection of his personal struggle but a rallying cry for justice and systemic change.

If you’d like to support Edwin’s quest for justice and freedom, you can contribute or share his story via tinyurl.com/FreeEdwinRubis.

Engaging with stories like his can help amplify the urgent need for sentencing reform, particularly as public attitudes toward cannabis continue to evolve.

This year is no different. No family gathering. No Christmas meal. No gifts from my loved ones. No visits.

The year 2024 is coming to a close, and the celebration of Christmas is here. Posters, billboards, the news media and magazines are all proclaiming, “Merry Christmas!” “Happy Holidays!” and “Season’s Greetings!” Many people are buying gifts for their loved ones; decorating and lighting Christmas trees; putting together prayer affirmations, meals, and other joyful activities to celebrate either Santa Claus, the birth of Christ, or for just simply being alive another year. Of course, there are those who don’t celebrate Christmas and choose to brush it off with a shrug.

However, there probably won’t be any such festivity for those in U.S. jails or prisons. Far from it.

December 25 has no joy for some of us who are incarcerated. Some may get drunk with homemade hooch, or get high on suboxone or K2 (the cheap drugs in prison) to numb the painful realization that they aren’t going anywhere during the Christmas holidays.

Fifteen-minute phone calls to families may only serve to make the day more stressful, because of the limitation of phone minutes the prison enforces. Not everyone in prison will receive holiday cards from loved ones due to prison mail restrictions, and because some of our families have forgotten us after being in prison for so long.

Our Christmas meal in prison has usually consisted of something along the lines of shredded chicken with a side of potatoes and green beans for lunch, and a peanut butter sandwich and apple for dinner — meals that are often cold and tasteless. Some of us will use our $14.60 books of U.S. mailing stamps (a common form of currency among those locked inside prisons) to buy bananas or plain lettuce salads that other prisoners will need to steal from the kitchen to make up for what the meal was lacking.

I know this because I have endured 26 Christmases behind bars. This year is no different. No family gathering. No Christmas meal. No gifts from my loved ones. No visits.

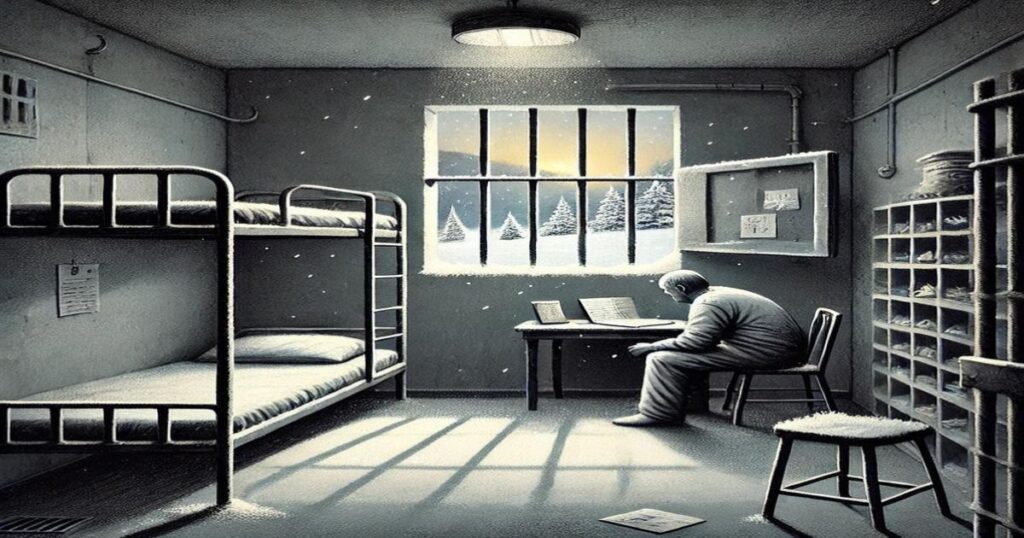

Instead, I will spend yet another day in a federal prison erected in 1938, high up in the mountains of Ashland, Kentucky, locked up in a 10-foot-by-10-foot prison cell, feeling the cold air streaming through a broken window sill, staring at the mold on the walls, smelling the foul odor emanating from the sewage of bathrooms that have been broken for more than a month, and resting my head on a paper-thin mattress laid on top of a metal bunk bed, which makes creaking sounds every time I move while sleeping.

How do I feel emotionally? I don’t. I am already accustomed to living without the conveniences of the outside world. I am used to living without laughter, without joy. The nearly 10,000 days of my imprisonment testify to this reality.

But regardless of how I feel, there are still small mercies and grace I can cling onto during the Christmas holiday. I can write a letter to my parents. I can call one of my sons, or call my grandson and tell him how much I miss and love him. I can call friends who still care about me. I can find time to pray for those who’ve been displaced in Ukraine, those who remain hungry in the Global South, and those who are sick in hospitals with terminal illnesses.

For the prisoners, the day will come and go like any other day of the year. We’ll spend it as much as we’ve spent the other holidays, and other celebrated days, stealing glances at one another with sullen faces, wishing we were somewhere else but prison.