Cannabis is woven into the cultural fabric of California generally and the Los Angeles area specifically, alternately glamorized and stigmatized through the music, television, and film that the city produced. The capitalists in town made money on both helping the government sell prohibition through the media, while simultaneously marketing cannabis as an accessory for goofy stoners, embarrassing burnouts, and beach bums.

That narrative began to change in the 1990s. Just as southern California hip-hop acts like Cypress Hill and Snoop Dogg introduced cannabis to a whole new generation, ground-breaking medical cannabis advocates were laying the foundation for what would set-off the most successful period of legal cannabis reform since prohibition began in 1937.

Dennis Peron, a Vietnam veteran who lost his partner Jonathan West to AIDS, organized Proposition P in San Francisco in 1991, a resolution that passed overwhelmingly declaring the city’s support for medical cannabis. In 1995 Peron would join with “Brownie” Mary Rathbun, Dr. Tod Mikuriya, Reverend Scott Tracy Imler, and others to organize Californians for Compassionate Use, a political action committee (PAC) that would author and lobby for the passage of Proposition 215. Voters approved the initiative 56-44 in 1996, making California the first state to implement a medical cannabis program in the United States.

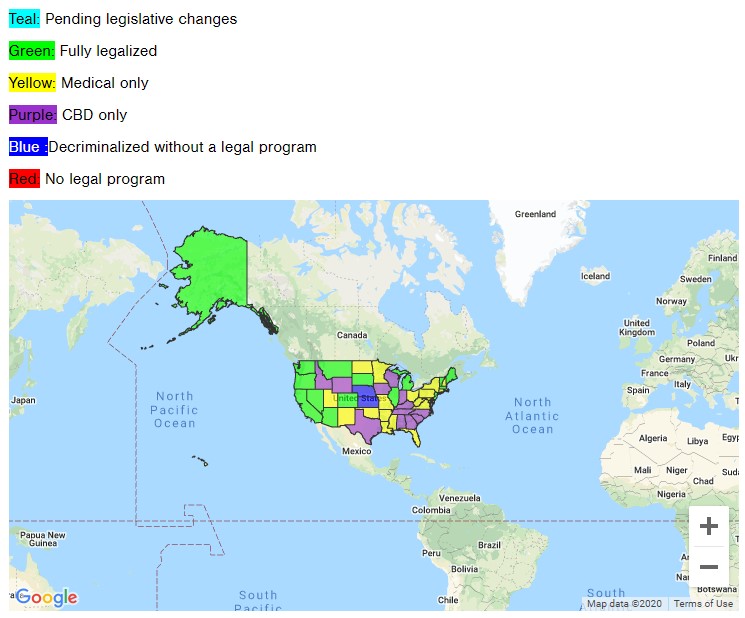

The success of medical cannabis reform in California would spur a state-by-state effort that now sees 49 states recognizing the medical value of cannabis in some form, with 92 million Americans living in adult-use jurisdictions.

From the beginning days of the fight for compassionate cannabis access, southern California never seemed to manifest the same level of support for patients that existed in the greater Bay area. Notable exceptions included the late Methodist Rev. Imler, who led the effort to create the “Sanctuary” in West Hollywood—with the eventual support of the mayor and sheriff—to serve cancer, AIDS, and other severely ill or terminal patients. Imler would go on to work with the city and Wells Fargo to purchase the property that would become the Los Angeles Cannabis Resource Center. The LACRC would operate until it was seized and sold by federal authorities under the George W. Bush administration in 2001.

The distinction between “medical”, “adult-use”, and “recreational” cannabis use has always been a false one—a clumsy attempt to create distinctions where there are none. Cannabis is not, in any compelling sense, like other “recreational” drugs alcohol or tobacco—two substances which are associated with the deaths of more than 550,000 people a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control. While people might self-medicate to some degree with both drugs, they are toxic with immense health risks and nearly zero medicinal value. Cannabis, by comparison, presents minimal risk and has provided millions of patients around the country with benefits they never experienced with traditional pharmaceuticals or other legal drugs like alcohol and tobacco.

There is a reason more than 1-in-5 veterans self-report using cannabis as a medicine. There is a reason why thousands of veterans all over the country have stepped forward to tell the same story to reporters, elected officials, and the public, about how cannabis helped them where cocktails of pharmaceuticals failed. That lived experience is echoed by the children living free from crippling epileptic seizures, those who have used cannabis as an “exit drug” from opioids, and the untold numbers of people who are finally able to have a full night’s sleep

Veterans have been among the most prominent patient advocates in the state, as seen through the work of Weed for Warriors Project and Operation EVAC (Educating Veterans About Cannabis) to provide consistent places of community and access to free medicine for thousands of veteran patients. Sweetleaf Collective, which has operated since 1996, has donated millions of dollars in cannabis to some of the most in-need and vulnerable patients, carrying on the tradition set by the pioneers of the movement to care for those suffering from cancer and HIV/AIDS.

Collectively these groups, along with long-time medical cannabis advocates including WAMM (WoMens Alliance for Medical Marijuana) founder Valerie Corral and the Santa Cruz Veterans Alliance, formed Team Compassion which successfully advocated for the passage of SB-34, the Dennis Peron and Brownie Mary Act., in 2019. The law removes certain disincentives and creates a pathway for legal operators to donate cannabis to patients.

The Veterans Cannabis Coalition, in partnership with Kannabis Works of Santa Ana and supported by regular donations from cannabis companies, have joined the effort and organized compassionate donations for veterans in Orange County since SB-34 went into effect in March. But while veteran and patient groups continue to organize to expand capacity and provide more medicine, every advocate in California recognizes they are barely scratching the surface of the overall need for quality, free cannabis medicine.

Many in the veteran and patient community in greater Los Angeles are in desperate straits—foregoing or limiting their cannabis use because of cost and turning back to cheaper pharmaceutical or to illicit drugs. Economic recession, COVID, and high taxes have all conspired to make cannabis even less accessible for those who rely on it most.

It falls to advocates and allies to create this change—and for the cannabis industry to put its money, time, and product where its mouth is.