Originally published by HiBnb.us

Tommy Chong Part 2: Blowin’ in the Wind

After less than 10 minutes with Cannabis comedy pioneer Tommy Chong, it’s clear that his personal and recreational paths are guided by the spiritual side of weed culture. His accomplishments — in music, stand-up comedy, and Hollywood — have surfaced as if predestined.

One of his greatest discoveries, he says, happened when fate led him to the philosophies of Joel Goldsmith, a philosopher, author, teacher, mystic, and spiritual healer. In 1951, Goldsmith established The Infinite Way which, as its homepage proclaims, “reveals the nature of God to be one infinite power, intelligence, and love; the nature of individual being to be one with His qualities and character, expressed in infinite forms and variety.” Chong recalls his first brush with the teachings of Goldsmith.

“I discovered The Infinite Way in the strangest way,” Chong says today, recalling the five minutes that changed his life. “I was walking to the gym in New York City on 41st Street, near where we lived. I had my gym bag, it was a nice sunny day and I got to 57th Street. Suddenly I literally felt something turn my body and push me toward HarperCollins publishing. I wasn’t intending to go there, but next thing I know, I’m in the door, then I’m in the bookstore and I felt some force pushing my arm down towards the shelf where I picked up the autobiography of Joel Goldsmith. I don’t think I went to the gym. I just got the book, took it home, and started reading. From that point on, I was a disciple of Goldsmith, one-hundred percent.”

The winding path of enlightenment Tommy Chong has taken from childhood to senior citizenship is, perhaps, best illustrated by the Buddhist idea of the twig in a river. The stick doesn’t enter the water and determine its path. It falls, perhaps from a tree, and then glides without effort, flowing wherever the current takes it. Sometimes it bangs against rocks before swirling around them. Sometimes it submerges momentarily before popping back up. Sometimes it swiftly glides, seemingly with great accuracy towards an indeterminate endpoint.

Chong hasn’t always been healthy and he hasn’t always been successful, but he learned from an early age to be content going with the flow. Embracing what the so-called enlightened folks today call, “mindfulness,” Chong has tuned in to forces he felt around him and followed paths that just seemed right to pursue. Flowing like a twig in a river has gotten him through his early years as an orphan, his early career as a musician, his breakthroughs in comedy, two battles with cancer, a nine-month-long jail sentence, and a career resurrection as he approaches his mid-80s (he’ll be 84 years old on May 24). As much as he credits Goldsmith and other philosophers, he also credits cannabis for tuning him into new frequencies.

“A lot of times, they send old people like me to what they call a rest home,” Chong says, then laughs softly. “The reason they call it that is [because] you go there and relax and get away from all the outside influences and pressures in your life. That’s what cannabis does. It puts you in the moment and that’s why you forget a lot of things. ‘What was I saying? What was I doing?’ You forget because you’re so in the moment, and when you’re in the moment, then your body’s in a natural state so it’s open to anything.”

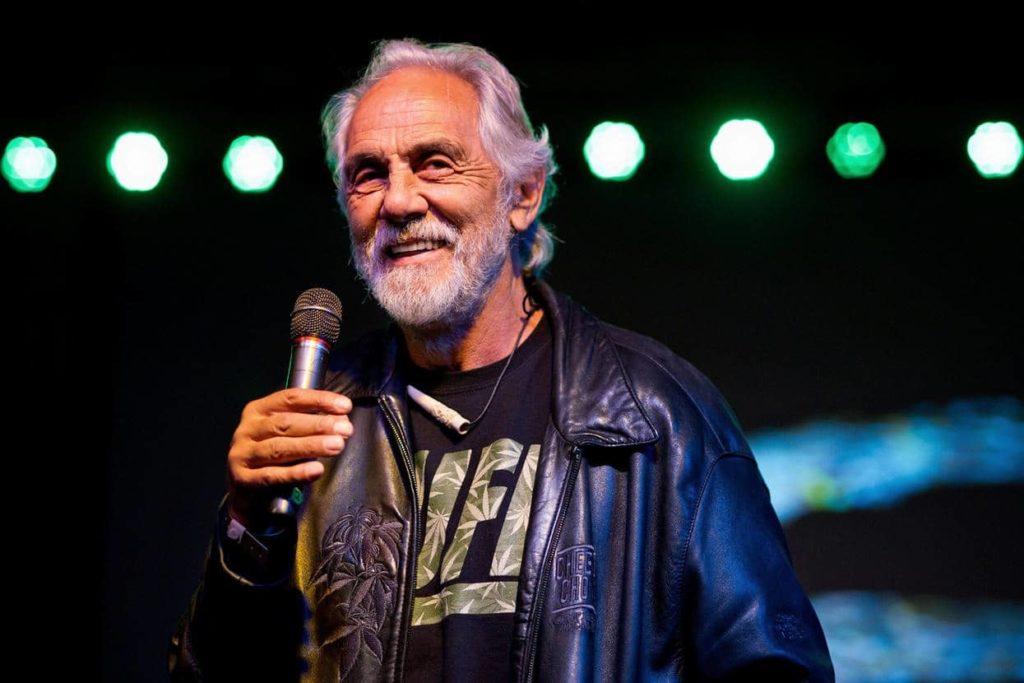

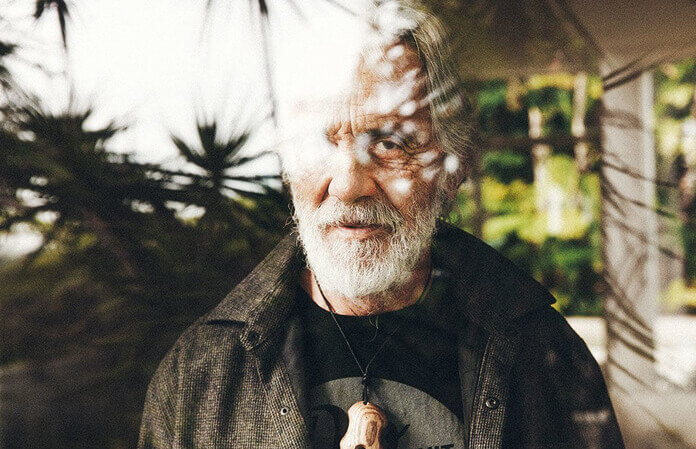

Tommy with Pipe 2019, photo courtesy of Tommy Chong

Can you remember your first experience with weed?

I was 17, trying to get through grade 11 and I was struggling. One day, I was just hanging out in Calgary with a jazz player by the name of Raymond Law. He had a Lenny Bruce comedy record with him, and he also had a joint. He said, “This is for you.” That’s what I mean when I talk about how serendipitous things are. I took a couple of tokes of the pot and put it out. And then I put on the Lenny Bruce and I heard the comedy and it blew me away. That was the basis for the Cheech & Chong world.

You and Lenny Bruce have very different styles of comedy. It’s interesting that it was him and not someone more outwardly provocative like Redd Foxx that roped you in.

I listened to Lenny Bruce every night for months. I’d take a toke and listen and absorb it and memorize. As a musician, you learn to memorize a lot. And that’s why I became a good actor. It was my music training. Because you gotta remember all those chords and all those notes and songs. And that’s how I could memorize sketches and jokes and learn how to do them. It was all because of my early music training.

We’ll get to music a little later. Once you discovered Lenny Bruce, did you decide to write jokes about weed and turning people on to cannabis?

I really didn’t know what I wanted. I just enjoyed what I was doing. But like I said, when you learn the secrets — the spiritual secrets — your life can be incredible. People always ask me, “Did you always know you’re going to be a comedian? Did you always know you’re going to be a movie director? Did you always know you’re going to write a book?” No, no, nothing. I just went from moment to moment. I learned to live in the moment because I had to.

What do you mean you “had to?”

My mother [contracted tuberculosis] and was quarantined in a sanitarium for five years, from the time I was three until I was eight and she got out. I spent a year in the hospital. They thought I had TB, too, but it turned out to be pleurisy and they cured me with a lot of needles in my butt every day. And then, I was taken from the hospital, put in an [the Salvation Army Booth Memorial Home for abandoned and abused children]. So, I’ve always been alone with myself. From that point, that’s the way it was. I had to live in the moment. And that’s one of the reasons I learned to be humble and smile. Because, when I went to the home I was too small to even make friends. But that was the basis of being alone and then finding out you’re not alone. See, when you’re in an orphanage there are certain times when you have to use muscle or you’re stuck. But for the most part, you’re under supervision, and the best way to exist under supervision is to be agreeable and try to be nice to everybody. And that’s how you make friends.

You had an older brother. Was he in the orphanage with you?

Yes, but he wasn’t like me. I was sick as a child. He was tough as nails. He adapted to his environment right away and he could fight so became my protector.

You were immersed in show business before you were 10 years old. Was being a performer a foregone conclusion?

My mother was very cultured and she had my sister take dancing most of her life. We’d go on the road with her when she toured with a little dance company. While she was doing that, I picked up a guitar and started playing around with it and it came naturally to me. It just made sense and that’s how I got into showbiz. We lived in the country and the fiddle player across the field from us found out I could play guitar. Next thing I knew, I was his guitar player. I was eight or nine years old and I started playing guitar at parties. And that was really important because it taught me about timing. If you want to be a musician you have to be really good with timing, and the same thing goes for comedy.

How did you evolve from being a guitar player in a fiddle group to being an established blues guitarist?

There was an Elvis Presley impersonator who heard me and I became his backup player. And then I formed a rock and roll band with my brother and his friends and that’s when I started playing blues.

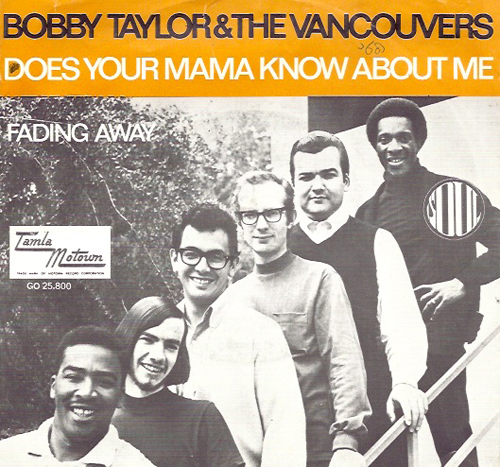

BobbyTaylor and the Vancouvers Album Cover

You were in the band Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers in the late ’60s, and while you started as a group that did covers by Motown acts, Motown founder Berry Gordy heard about you and signed you to the label. You even co-wrote the band’s debut single “Does Your Mama Know About Me,” which climbed to number 29 on the Billboard Hot 100 and number 44 on the Canadian charts.

I could have stayed with Motown forever. But I got fired — not by Berry Gordy. He was still a good friend of mine. We were deported back to Windsor from Detroit and when that happened I told Motown I needed a green card to get back into the States. And they didn’t know what that was so they contacted their lawyers and the lawyers said okay. They set up a meeting for me with the immigration people, who wanted to meet me at a certain time. Unfortunately, it was right when I was supposed to be at a gig. You can’t miss those immigration meetings at all or else they put you at the back of the line. So, I missed the gig instead and when I went back to Detroit I brought the bass player with me. I thought, “They’re not going to fire the both of us.” And they didn’t. They just fired me!

But you stayed close to Berry Gordy?

Oh, yeah, man. When he found out that I was fired, he said, “No, no, you’re not fired.” But then I told him, “Look, it’s okay. I don’t want to work for Berry Gordy. I want to become a Bery Gordy.” And he knew what I meant, so he gave me a nice severance payment, and away I went.

Did you go right into comedy from there?

I had to go back to Vancouver. I had no gig. It was literally the first time in my life that I wasn’t playing onstage with my guitar. But that gave me a chance to work. I became a light man for the strip club my family-owned. I studied that space and I said, “Wow, that would make a great improv club,” having the girls as actresses as opposed to dancers.” We did that and then I met a great guitarist from Edmonton — again, serendipity, the powers that be put us together — and, he convinced me to give up the guitar as a means of employment because he was probably the best in the world and he was at the end of his life. He died penniless. Not only penniless but he was being insulted.

How so?

He was so talented. He was a great player and they just paid him a hundred dollars a night to come onstage and do solos. But he could do anything. He wrote a lot of the comedy that Cheech & Chong ended up doing. And it’s so funny because that’s the guy that turned me onto the I Ching.

Cheech Marin left Southern California and came to Vancouver in the late ’60s to avoid getting drafted for the Vietnam war. How did the two of you hook up and did you immediately bond?

We kinda did, but we’re complete opposites, man. Cheech is very studious and I’m as flighty as can be. I’m Gemini and he’s Cancer. From the first time I met him, he had this cocky attitude. And then we talked a lot at the club and we realized we could do this thing there together. So that’s where we started. And when I realized we could really be comedians together — Cheech was always convinced, but I wasn’t as sure — then, when I had a chance to make a choice, my spiritual training commenced: “Go to California.” So I did. Cheech didn’t want anything to do with L.A. but I knew that’s where we had to go to be Cheech & Chong. He wanted to stay in Canada, but I said, “We gotta be comedians, not Canadians.” So we went to L.A. and performed everywhere we could and it all grew from there.

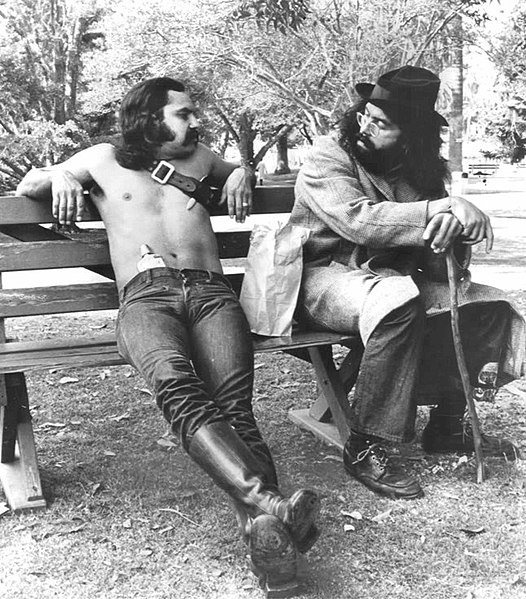

Cheech and Chong 1972, William Morris Agency (management), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

We got caught a few times. There was a time when I used to carry a couple of joints in these pen caps so I could always find them when I wanted a joint. One time when we were pretty well known, we were packing up stuff and getting ready to go to the States. I put these pen caps on the dresser and finished packing. My wife saw the pen caps and thought I had forgotten them so she put them in my bag. Of course, I didn’t know what she had done. So when we got to the border they opened my bag and there’s a pen cap.

It was kind of funny. The guy opens one up and comes up with a joint. He turns to me and says, “What’s this?” So, being a comedian I said, “I guess it’s another day in Winnipeg.” The guy takes us to the head cop and says, “Hey look, sir. I found this marijuana.” And the guy goes, “Wow, look! You’ve got one whole joint. Do you know who that is? That’s Cheech & Chong. Get out of my face.” And that was the end of that.

In about 1990, I started doing stand-up comedy by myself so I did a lot of traveling. One time, I got caught at the airport in Canada with some weed. I used to put it in my guitar case. I carried the guitar on my back and the weed was way behind my head so if there were dogs sniffing around they wouldn’t find anything. But this time I forgot I had a pipe in my pocket. So, I see a dog and I figure there’s no problem because I’ve got my guitar case. And right away, he puts his nose in my crotch and I was, like, “Oh, shit, I forgot about the pipe.”

The authorities made a big deal out of it. They said I had to give them my passport, so I did. They went in the back to figure out what to do with me, and then they came back very sheepishly because I had an American passport. I was born in Canada, but I was American so they couldn’t keep me out of Canada. That’s what they were trying to do. I said, “So, I can bring weed across here any time I feel like it?” They didn’t think that was so funny.

You might be able to get away with smoking weed during a shoot now, but back when we did our movies, weed was still quite illegal. There was no smoking on the set. We used fake smoke for the camera. And between takes, we’d go around back or in a car, and me and Cheech… I always had a joint, and he always went, “Hey man, you got one?” So we’d do a little bit. Sometimes it would fuck up the movie because we’d miss our cues.

No, I never bought into it. When you do a movie you become that character. And that character is only good when it’s working. When it’s not working, then you’re just you. That’s why a lot of people get fooled by actors. They see them on screen and they’re so articulate and beautiful. They have all the answers to everything because they’re acting from a script. But when you get them off-camera, a lot of them don’t have a clue about anything. And they’re wackos when it comes to political things. Our thing was a little different, but it’s not a world I’d like to spend a lot of my time in.

There’s been so many of them. It’s so hard to pick one over another. I think more than anything, it was really satisfying to direct the movies. I had a lot of power. For instance, when Cheech would talk about Timothy Leary, all I had to do was make a call and we got Timothy Leary on the set. The power of movies is incredible. Being in L.A., I’ve met so many celebrities, man. People ask me about my bucket list of people to get high with. It’s still Paul McCartney. I’ve gotten high in the presence of every Beatle and the one Beatle that smoked with me was George. He and I shared a couple of joints over the years, but never Paul. He’s really the only one on my bucket list. It’s more like a tin cup list.

I was kind of warned or told that I was going to go to prison. But I was in denial until I was ready to be in front of the judge to be sentenced. Going to jail for selling a bong? that didn’t compute. But then I accepted what was happening. I was faced with the same kind of cold, hard facts as political prisoners because that’s what it was with me. The situation was purely financial and political because I was promoting a substance that the industry didn’t want. I’m very pragmatic. I adjust well.

I mean, not really because I’m an actor too and improvisation is really my thing. So I’m good at reading situations. When I went to prison I got offered weed the minute I walked in there. But then, I also got drug tested every time someone would offer me something. So, they were obviously snitches. I never smoked anything for three years. I stopped smoking a year before I went in, and during the nine months I was in there I didn’t have any. And then the year after I got out there were all these rules I had to abide by because I definitely didn’t want to go back to jail.

I’m cancer-free, thank God, and I feel great. I honestly believe that cannabis calms the mind and once the mind is calm, then your immune system kicks in. But if your mind is in fight or flight mode, the immune system doesn’t really activate the same way. If your mind is active and ready to be attacked, that’s when illness can strike or, you can stop healing. Also. You gotta remember that we’re not here forever. And whenever the body gets a hint that it may be getting ready to shut down and stop working then everything, all the stuff in your body starts failing and stops doing its job. The first one stops its job, then the other. Everything kicks in. But with cannabis, there’s no fight, there’s no flight. The mind is calm and the body can do its magic and heal itself.

Of course, because it gave me everything I was missing. It gave me an appetite because when you’re on those drugs a lot of times you feel nauseous or you just don’t feel like eating. You have to eat to gain strength to fight an illness. Or it put me into a state where I could just chill. After you have a major procedure, doctors sometimes put you into a coma. You check out, shut the fuck up, and let everything heal. That’s what cannabis did for me.

I mean, I don’t know. I wouldn’t want to say let’s get rid of proven medicines like antibiotics, heart medicines, and other things like that. To a certain extent, I think cannabis works if you believe it works. It’s definitely a great medicine for a lot of people, not just alone. But the human body itself is so incredible, especially the mind.

I think it doesn’t work for everyone, but I’ve learned anything that puts you close to God is good. When you get close to God it’s like tuning a string on a guitar. You wind it and you can feel the change and when you get a string in perfect tune, it’s pure. It resonates and it’s wonderful. And then when you get all six strings in tune and you hit the right chord, oh my God, It’s so beautiful and spiritual.

About the Writer

Jon Wiederhorn is a veteran author and journalist who specializes in books and articles about music and entertainment. His book credits include “Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal,” “Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen,” “I’m the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax” and “My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory” He has worked as an associate editor at Rolling Stone, Executive Editor at Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. In addition, Jon’s work has been published in Entertainment Weekly, TV Guide, Guitar World, Revolver, and many other publications. He also wrote and hosted the iHeart exclusive 12-episode podcast “Backstaged: The Devil in Metal.”

Written by: Jon Wiedehorn

https://www.hibnb.ca/read_hi/tommy-chong-part-2-homelessness-to-hollywood/